In 1993, my 19 year old brain latched on to a movie character and wouldn't let go. Now in 2015, I rewatched to find out why.

In 1993

autism was considered a rare condition that was little understood. Few English-speaking mental health professionals had even heard of its higher-functioning form,

Asperger Syndrome, because it wouldn't be in the DSM (

Diagnostic and Statistics Manual) for another year.

Nevertheless, writers and actors excel at capturing the human spirit. That year, a movie came out that accurately depicted high-functioning autism and directly combated ableism (harmful beliefs about disabled people) in unambiguous terms.

Benny & Joon is unique. How often are two disabled people allowed to fall in love

with each other on the big screen? This may be the only autistic romance movie in existence.

If you are autistic,

Benny & Joon offers validation, empowerment, and positive self-image. If you know an autistic adult or child, this movie should add depth to your understanding of them. And if you never expect to meet an autist, well,

statistics are against you, but at least watch it to have your heart warmed and your awareness expanded.

It saddens me, however, that certain critics somehow found Benny & Joon problematic. Throughout this post, I will directly answer the points made by one of these reviews.

Spoiler warning: This review reveals plot points and thematic arcs, but don't worry. The formulaic storyline is already somewhat predictable; the joy is in seeing it played out on screen by interesting characters. You might even enjoy it more by having this autistic lens to view it through.

Why My Brain Latched On and Wouldn't Let Go

When I first saw this movie, I didn't know that 18 years later I would be diagnosed with Aspergers. But my subconscious knew that Joon was like me. I loved Joon. I admired her. I related to her.

I identified with her odd little mannerisms, and knew that, deep down, I wanted to hold the same flat affect on my face and make those jerky, birdlike motions. Her descriptions of the world mirrored my own strange ways of thinking. Her outbursts and unusual speech patterns reflected an inner persona I was holding at bay, like I had this little bit of crazy locked up inside that escaped sometimes when no one was looking.

Shortly after seeing the movie the first time, I had a dream. It was of a blond girl, dressed in gray, running nimbly along the top of a castle wall. When she reached the peak, she jumped.

And I awoke.

I knew instantly that she was inspired by Joon. There was this deep sense that the girl was incredibly smart and talented, and yet she was also mentally immature, restricted, and damaged in some way.

It inspired a novella I wrote about a princess kidnapped into slavery, and her will is beaten out of her. She is rescued in adulthood, but never lost her stunted naiveté juxtaposed against a keen mental acuity.

When I finished writing, I realized it was an autobiography: a metaphorical account of my own abuse by teachers and peers, an allegory of the way the world misunderstood me and of all the messages from a world that told me I was crazy and broken.

|

I even borrowed a few decorating tips from Joon.

Colored bottles, knickknacks, brightly colored wispy fabrics.

This is basically my room. |

Looking back, I can see just how validating this movie was, and how beneficial it was to my own development.

Movies like these give millions of undiagnosed autists something to connect to and a way to feel valued when the rest of the world is marginalizing us for being different.

Evidence of Autism

The movie refers to Joon simply as "mentally ill", and doesn't comment at all on Sam's condition. In 1993, "mentally ill" might have been the only diagnosis available for a high-functioning autist. So we're left to speculate.

The most common armchair diagnosis I've seen online (aside from autism) is that Joon is

schizophrenic, and that Sam is "quirky". Perhaps this is because autists are often not thought to be capable of creativity, and since Joon is a painter, she must be schizophrenic?

|

So much creationizing!

And paintifying! Look at all that paintifying! |

Misconceptions like this pervade both society and the medical community, which is one reason it took me so long to look into Aspergers for myself. Like Joon, I was merely "quirky" with a tendency towards "mental illness" that I kept under wraps.

Autism traits tend to vary widely from person to person, some even manifesting in opposite ways. Many traits haven't been studied and are not part of official diagnostic manuals. When you read about autism long enough and learn about some of the root causes (like sensory processing issues), you start to notice patterns.

Let's consider Sam first. Here are his

autistic traits that jumped out quite starkly:

Joon's list is longer; she's on screen more.

- Sudden outbursts, bad enough to chase away housekeepers (aka caregivers).

- Needs things to be just right or she has an "episode".

- Picky about housekeepers. Joon rejects them for a long list of imperfections. One committed sins of metaphor, and another, "her hair smelled". These indicate sensory processing issues and a need for certainty and literalism.

- Seems comforted when she's painting.

- Particular about food.

- Wears a helmet when riding in the car.

- Shows deep creativity and intelligence but no one takes her seriously.

- Fascinated with fire (for similar reasons why some autists are fascinated by water – watching the flow and movement).

- Doesn't get along with peers (according to her doctor).

- "Her stress level is always a factor in her display of symptoms," according to her doctor.

- Gets hung up on moral details which results in outbursts of anger (moral rigidity).

- "Her routine is everything to her," Benny describes to Sam.

- Notable stimming (self-stimulation, like rocking or shaking a leg) when she's nervous.

- Talks to herself. At some point Benny says that she hears voices, but as it's depicted on screen, it could easily be echolalia, or repetitive vocal stimming.

- Nearly has a meltdown when Sam plays loud rock music (sensory processing). She takes away his radio. Later, she has trouble articulating the experience, particularly what she was seeing and hearing, which indicates that her verbal skills are conditional.

- Kicks Sam out for "cleaning the house." Probably because her things got moved — highly anxiety-producing for many autists.

She has other traits which are more difficult to describe. For instance, she may have a form of

synesthesia, which is common in autists, as evidenced by a scene in which she describes how the raisins in her pudding must feel emotionally. Many autists

sense that objects have personalities, either to a mild or extreme degree.

There are only two times when she breaks with autistic behavior.

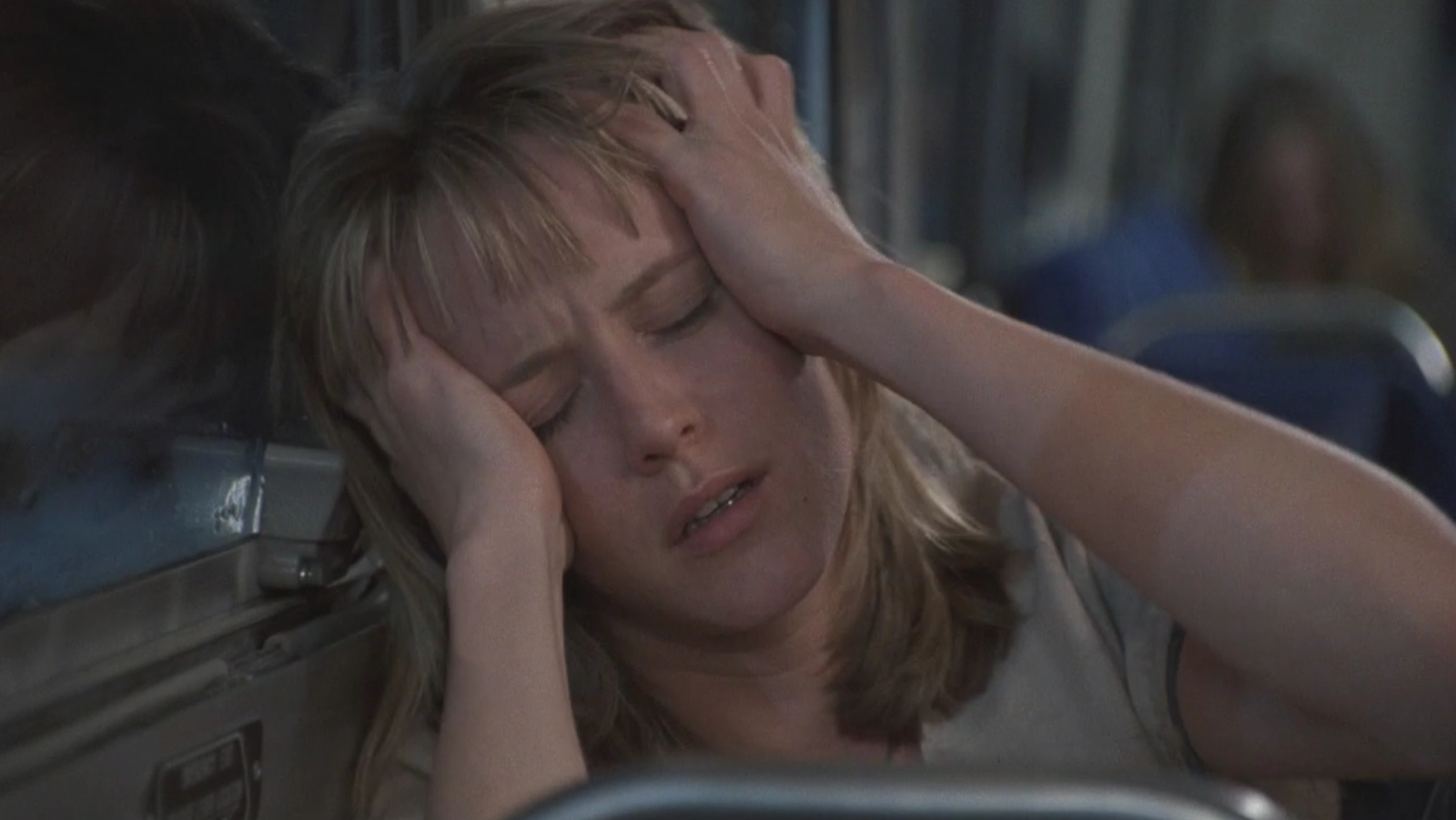

|

| STOP: Not typical autistic behavior. |

At one point, she stands in the middle of the street and "directs traffic" with a ping pong paddle, and acts totally detached from reality. To be very clear, this is not something a typical autist would do, but might be more in line with schizophrenia or

bipolar in a hyper-manic phase.

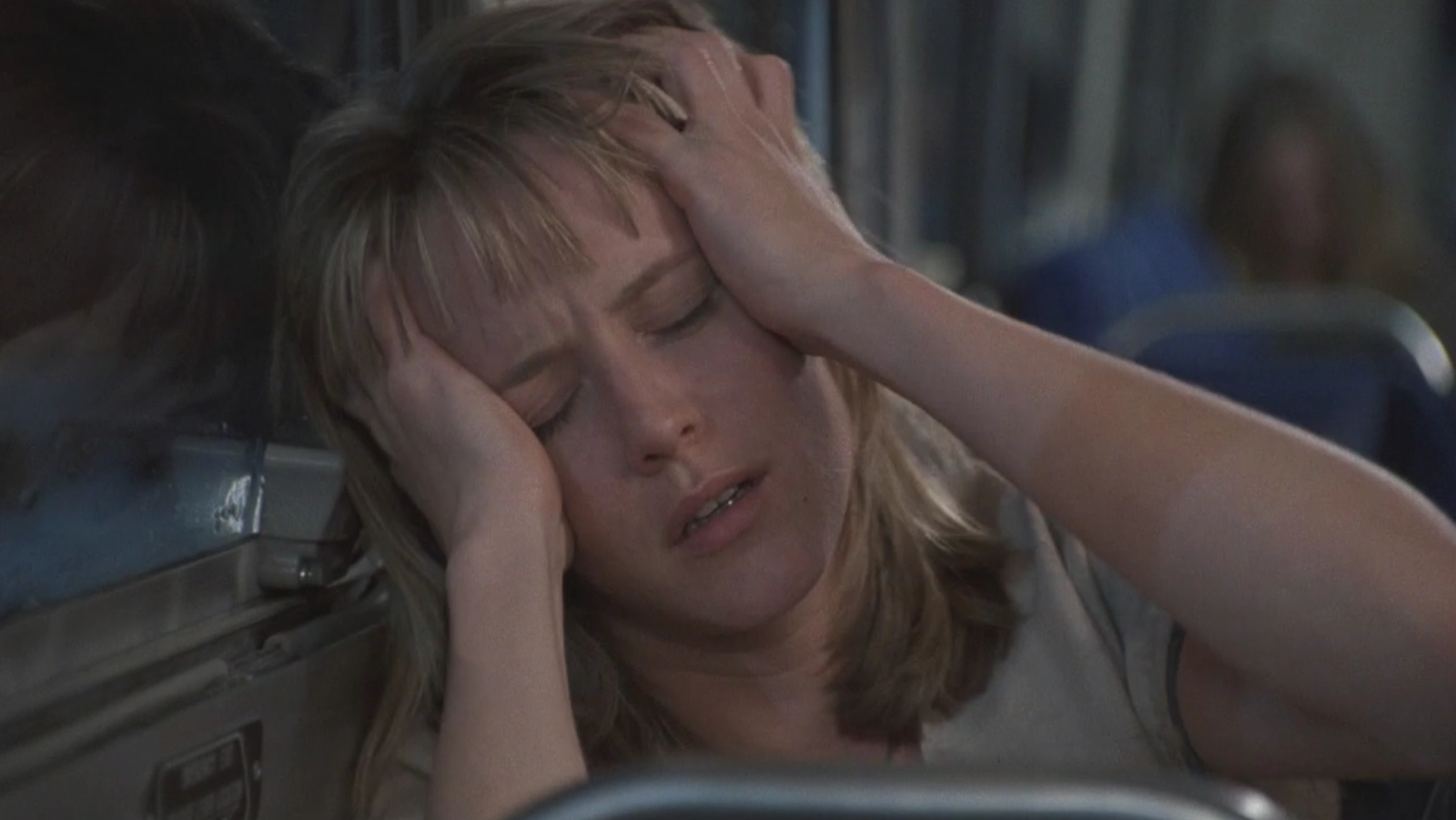

In another scene, she melts down on a bus in a high-stress situation. Initially, her behavior is in line with an autistic meltdown (including rocking and hand flapping). But as the tension heightens, she becomes paranoid. Such behavior could stem from an extreme meltdown, but not typically.

These exceptions can be explained either by

comorbidities (other conditions that occur alongside autism), or as necessary additions to drive the plot.

A Positive Portrayal

|

| Autistic people are capable of love, happiness, creativity, and agency. |

Overall, the film portrays autism in a positive and realistic light, neither overly glorifying it, nor bemoaning our miserable fate. It grapples with real issues that autists and our caregivers or family must face, and manages to frame it in a light-hearted comedy. The theme comes across strongly and can be summarized in this sentence:

"Disabled people have the right to make their own choices."

The movie represents autists as human and promotes

neurodiversity, highlighting the value we can provide to ourselves and those around us, even to those might otherwise see us as useless burdens.

Moreover, Benny & Joon:

- depicts autists as capable of love and deserving of a love life;

- depicts autists as capable of happiness, even when we're not "productive" by societal standards;

- portrays a loving sibling relationship with an autist, where her brother is (for the most part) good to her. (Contrast this to the sibling relationship in Rain Man.)

Romance

The romantic arc truly sets this film apart. It doesn't merely depict a successful autistic love relationship; it goes further, contrasting it to Benny's neurotypical romance with Ruthie.

|

| Chemistry so powerful you can reach out and touch it. |

Sam and Joon's chemistry is palpable — innocent and enchanting. They seem to communicate without words. Each seems to have finally found a kindred soul, and, though neither has any experience with love, they take their first steps with grace, with no hint of shame or self-consciousness.

In contrast, Benny and Ruthie's chemistry is awkward. Joon and Sam are far more socially capable (with each other) than the

allistic (non-autistic) leads, who are constantly fumbling. Their barriers to love center around miscommunication and a lack of self-awareness.

|

Things are just not coming together for these two.

These scenes are literally back to back. |

This is a reversal of the standard expectations and it filled me with glee. It reminds viewers that allists can also be poor at social interactions and

empathy, even with each other.

I often say that autism is characterized by extreme mental strengths and specializations juxtaposed against extreme mental deficits. Particularly sweet is how Joon and Sam's autistic extremes compliment one another, each filling in the void left by the other's weaknesses.

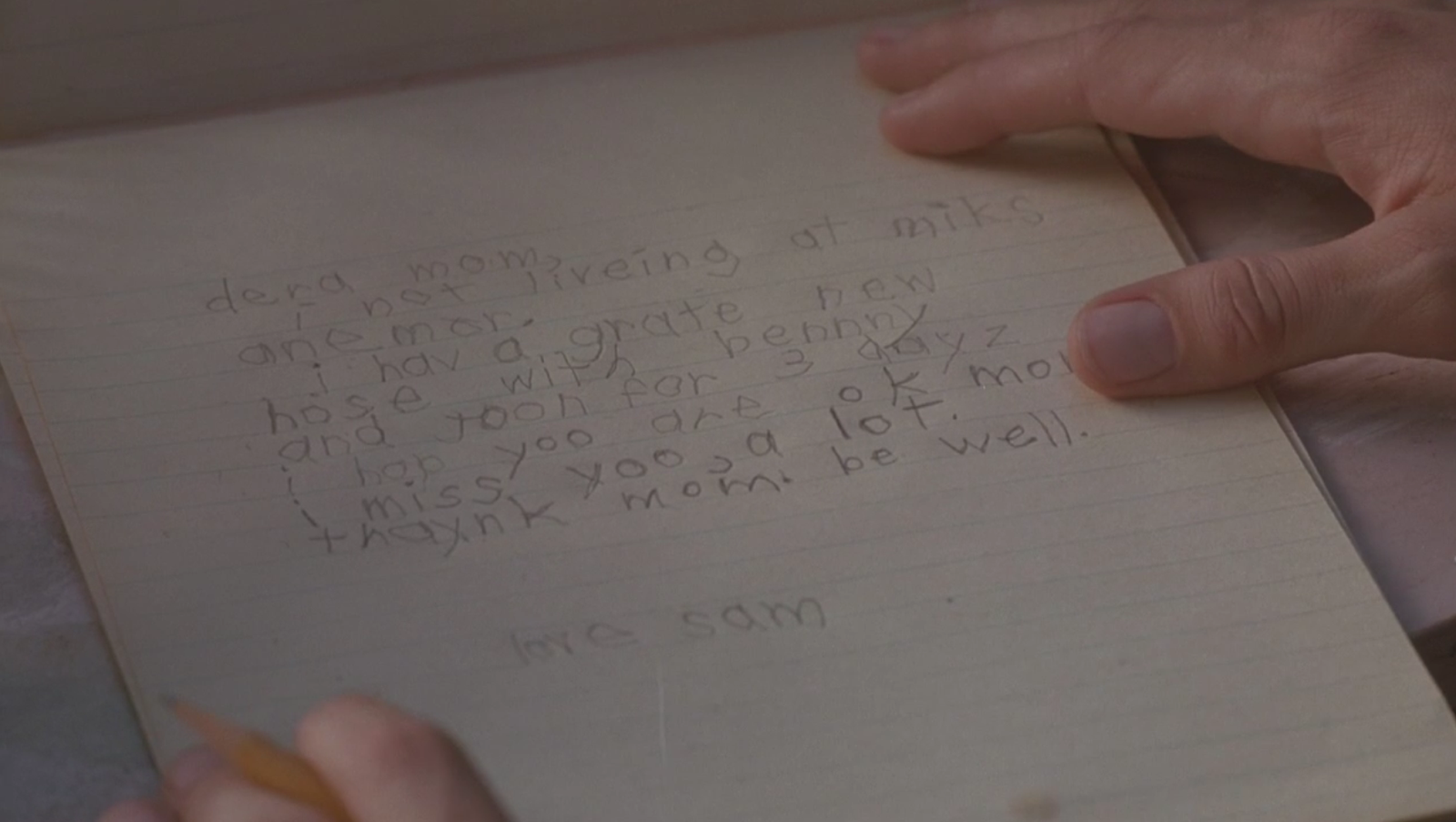

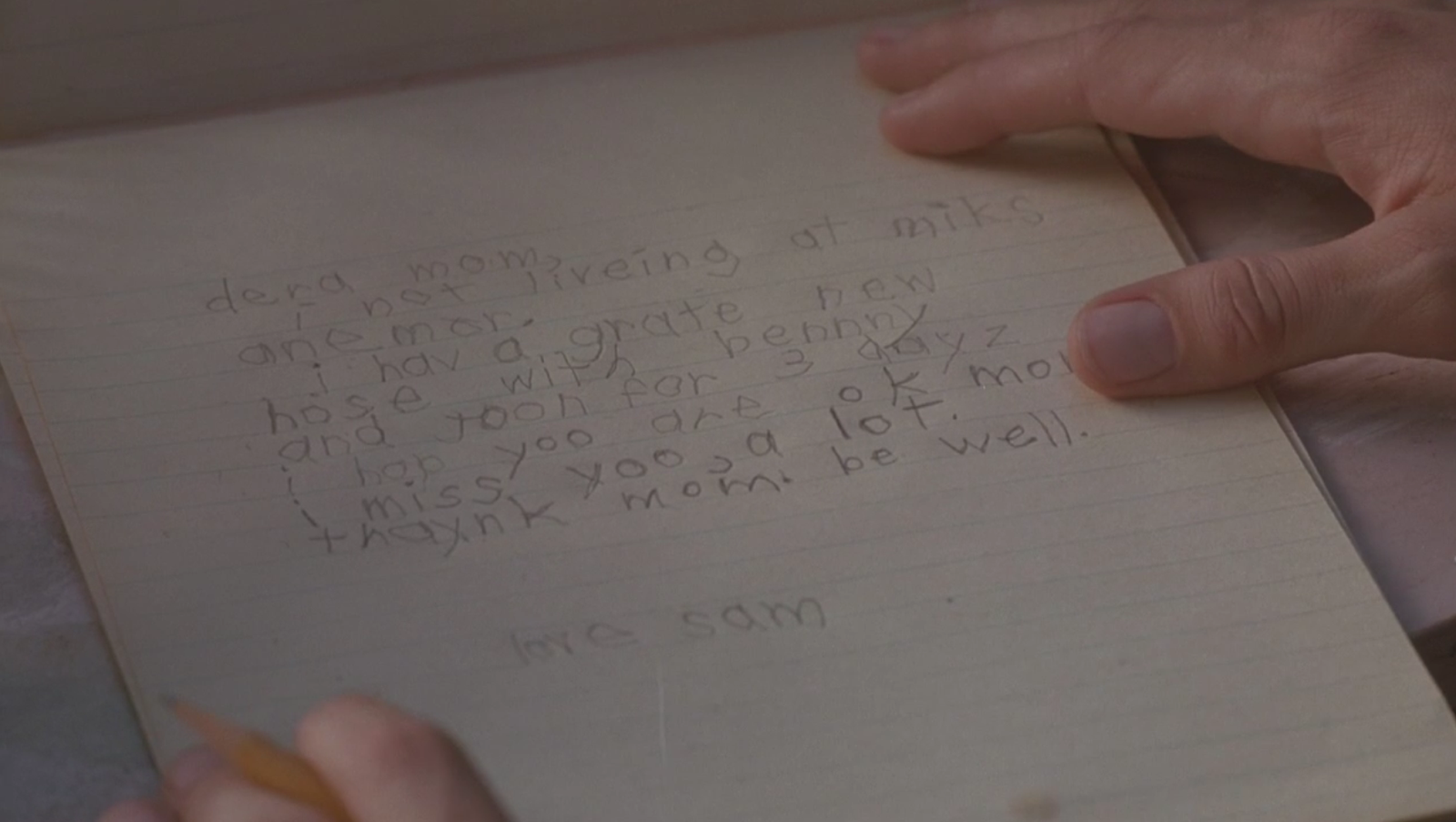

In one scene, barely-literate Sam tries to write to his mother. Joon rewrites the letter with

hyperlexic skill.

|

One of the harsh realities of autism depicted here.

Writing is difficult for many on the spectrum,

whereas it comes easily to others, like me. |

She's got problems of her own, though. For instance, she is sloppy and disorganized. He cleans the house with acute, almost obsessive, attention to detail. In spite of her initial distress, she warms to this pretty quickly.

Is Autism A "Disability"? Or A Difference In Cultures

The story argues for what many autists already believe: that most problems associated with autism aren't intrinsically caused by autism itself. They are more often caused by neurotypical expectations that autists are unable to meet, in an environment that is set up exclusively for neurotypical success.

Every conflict Joon or Sam have is with the world, not with themselves or with each other. Individually, Joon is happy; Sam is happy. And they're happy together.

All of their problems are caused by allists: the endless stream of housekeepers who can't get along with Joon, the doctor who wants to send Joon to a group home, and the overprotective brother who won't let her make her own choices. It's a world in which their talents — her art and Sam's performance comedy — aren't appreciated — at least not enough that anyone will give them a living wage.

While Benny and Ruthie struggle to hook up, Joon and Sam progress blissfully and problem-free. No significant misunderstandings, no hidden defensiveness. You get the sense that if they could live on their own little planet, they'd be perfectly functional.

This is a sentiment expressed by many autists. We feel like we were born on the

WrongPlanet. Our most distressing symptoms come from living in an allistic world trying to conform to a neurotypical culture.

|

The application process almost proves to be an unbeatable obstacle,

as it is for many on the spectrum. |

Sam eventually uses his expertise and passion for movies to get a job in a video store. Many autists struggle to feel like their idiosyncratic special interests are useful, but he figures out how to make a living at it. This isn't possible for all autists, but it's at least one role model in a world with none.

It sends a message to society: Don't underestimate us. We have skills. Maybe not the exact skills you want us to have, or we might be rough around the edges, but widen your view and you might be surprised.

"Patronizingly Adorable" or Patronizingly Keeping Us In Our Place?

The author of the piece is bipolar, which makes her an authority on

invisible disabilities in general, but it does

not make her an authority on autism. Just to make it clear: being one neurotype does not make you an expert on other neurotypes. I live with a bipolar woman, a couple of

OCDs, and another aspie. I'm careful to never assume their experience.

Even though she concludes that Joon is autistic, Tibbetts insists on using the word "schizophrenic," as if the two neurotypes are interchangeable. It's frankly offensive… probably to schizophrenics, too.

|

| This? Is not a "tantrum." |

"Tantrum" implies a childish, manipulative call for attention. In reality, a

meltdown is a sensory overload that floods our brains with panic or emotional overwhelm, leaving us with little control over our bodies or speech. I tell people a meltdown is like an emotional seizure, and they should treat it like a medical problem. It's poor allyship to perpetuate this marginalizing stereotype.

Her review flies under the flag of false advocacy. Her outrage at

Benny & Joon reminds me of the

Derpy Hooves controversy, where parents of developmentally challenged children found the My Little Pony character offensive, and protested to get her edited out of the show. In contrast, the

majority of actual autists felt personally attacked. A character we related to was made invisible by our supposed allies. By deleting Derpy, they deleted us.

Save Derpy

I dare you not to cry.

These patronizing, chivalrous, well-meaning allies are Disability Ventriloquists, because they think we're dummies and they try to speak for us. We remain dehumanized, pawns without agency, moved around on the chessboard by whoever speaks for us the loudest.

|

I am not your dummy.

#ActuallyAutistic |

But I'd like to thank Ms. Tibbetts for being wrong, because she provides a good counterpoint for a detailed look at what this movie does right.

Too Adorkable? Oh noes!

The Bitch Flicks review takes greatest issue with how Benny & Joon presents autism:

"There is NOTHING 'adorable' about mental illness… [This movie] trivializes and downplays a serious, crippling disorder."

Ahem.

First, autism is not a "crippling disorder," which is a point made within the film itself when Benny repeatedly underestimates Joon's and Sam's capabilities. For Bitch Flicks to perpetuate this stereotype in the face of a film that attempts to dismantle it is the pinnacle of ablism.

Secondly, Benny & Joon is a comedy. Its job is making us laugh.

Nevertheless, the darker aspects of autism are explicitly portrayed. Benny's life is severely impacted by having to take care of his sister. Sam is grateful to sleep on Benny's couch because his cousin had him sleeping under the sink. Joon nearly burns the house down a couple of times. One of her meltdowns is so uncomfortably and realistically depicted on screen that tears came to my eyes.

|

This living situation is an improvement over

sleeping under the sink. |

Autistic life sucks, and this movie gives us glimpses of these harsh realities lurking there beneath the surface.

But life as an autist is awesome, too. We are quirky, fun-loving, talented. Yes, we can giggle and paint and be silly. When we're given full freedom to express ourselves, life is an absolute joy to live, both for us, and for our loved ones.

Should we be condemned to misery, even in fiction, because disabilities are Serious Business? Are we to only have depressing horror films made about us? Is neurotypical society only allowed to see what a burden we are, and how unredeemable and useless we are? Are we supposed to have every light-hearted happy-ending stricken from our collective consciousness?

Problematic? You Don't Get How Stories Work

Some social justice media critics think that if any character acts badly, the whole story is problematic.

I want to destroy that idea right now.

|

| Ka-boom. |

Problematic behavior exists in real life, and it therefore should be depicted in fiction.

Why? Because those who experience these situations in real life need something relate to. And those who commit harmful behaviors need to see the harm they cause.

I wish more social justice champions understood how how plot and theme work. Here's a quick rundown:

As Robert McKee points out in

Story (a how-to book for screenwriters and novelists) a theme is an argument between two opposing values, which builds, until it reaches a final conclusion.

It's a debate: a fictional argument. You have to show characters acting in opposition. Who will turn out to be right? The story must depict the tragic results of acting on the opposing value. If no character behaves badly, the conclusion will ring hollow.

If you make a movie to combat ablism, you must depict ablism. To make a movie combatting sexism, you must portray sexism. To make a movie against racism, you've got to show some racists. Otherwise, you have a boring, unconvincing movie where nothing happens. And if we successfully remove these types of problematic content from our fiction, our movement will fizzle out and die.

|

Combatting oppresssion

through the power of creativity |

So the real proof of a problematic story is in its ending.

We can tell by the ending that the theme of Benny & Joon is, "Developmentally disabled people are capable of, and have the right, to make their own choices."

The movie refuses to justify Benny's abuse of Joon and Sam. It condemns his behavior and then offers him redemption in a very simple form: Stop treating your sister like a child. Let her grow up and follow her own path.

An ableist movie would have sent a smiling Joon off to live safely ever after in an institution. The theme would concluded: "Disabled people cannot think for themselves, so they should live out of sight lest they offend our sensibilities or hurt someone."

Sadly, it seems that Ms. Tibbetts might have preferred that message.

What Seems Problematic Is Actually Good Storytelling

Benny has taken care of his sister since their parents died. He resists putting her in a group home because he thinks she won't be happy there, and he wants her to have some level of independence. This is admirable.

But he isn't perfect. He is patronizing and overprotective. Moreover, he's in the difficult position most caregivers are: It's hard to care for someone with special needs. It sets limitations on his free time, money, social life, and energy. He's under a constant emotional drain.

According to Tibbetts, "Benny & Joon deals far more with Benny’s 'unfortunate' situation of having to care for his sister than it does with Joon herself. Yes, although it does speak to Joon’s creativity, her spirit, etc., it doesn’t address the fact that Benny's kept her infantilized most of her adult life."

Firstly, the stress of caregiving shouldn't be so flippantly dismissed. It's clear in this movie that Benny simultaneously loves his sister, enjoys her company, and is becoming resentful of the distress she causes him. This is a realistic situation, and an understandable reaction. As an autistic mother with autistic children, I know this all too well.

Secondly, the movie does far more than address Benny's well-intentioned but misguided mistreatment of his sister. This is, in fact, the whole point of the movie, as is shown through dialog, over and over again.

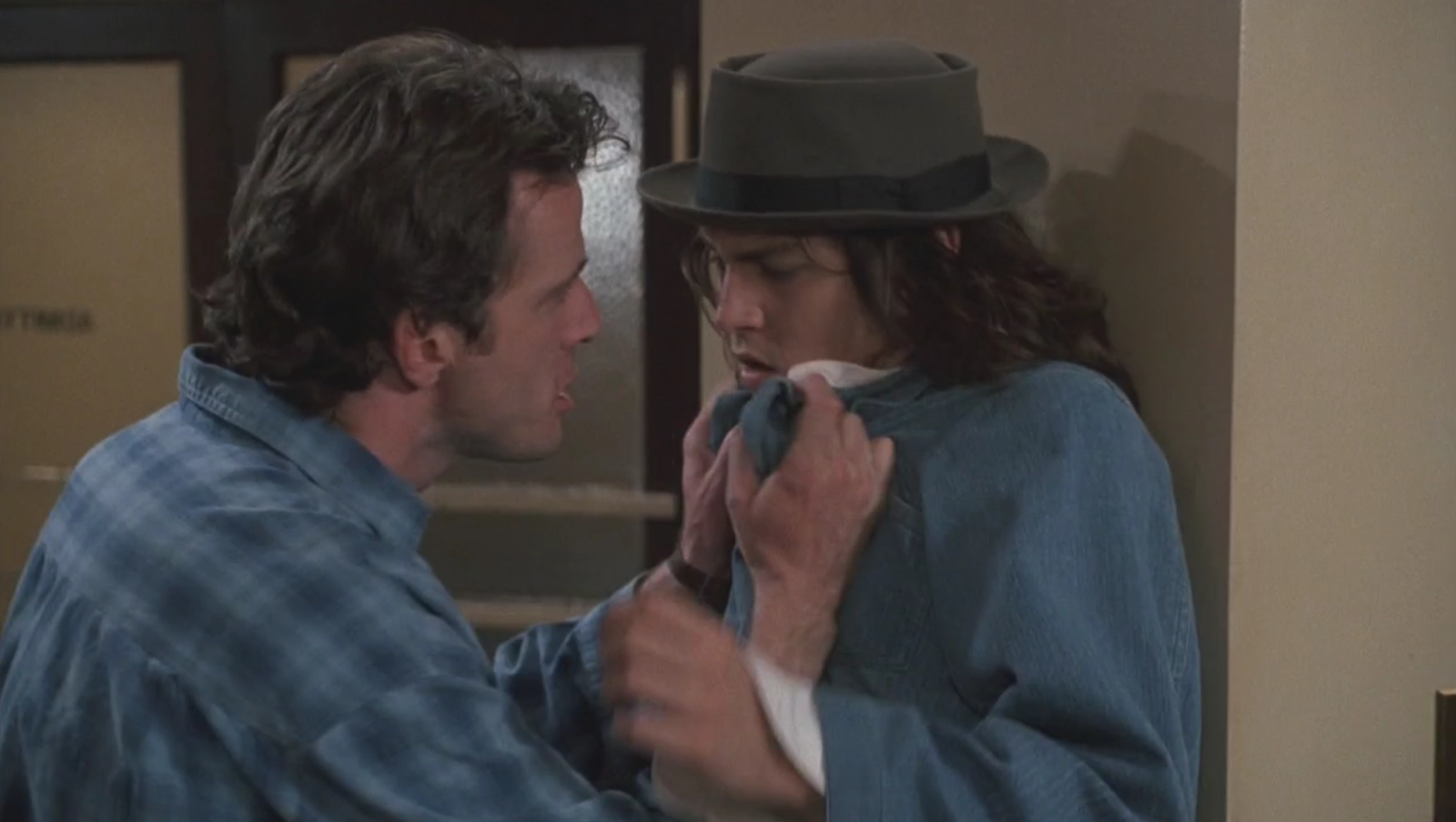

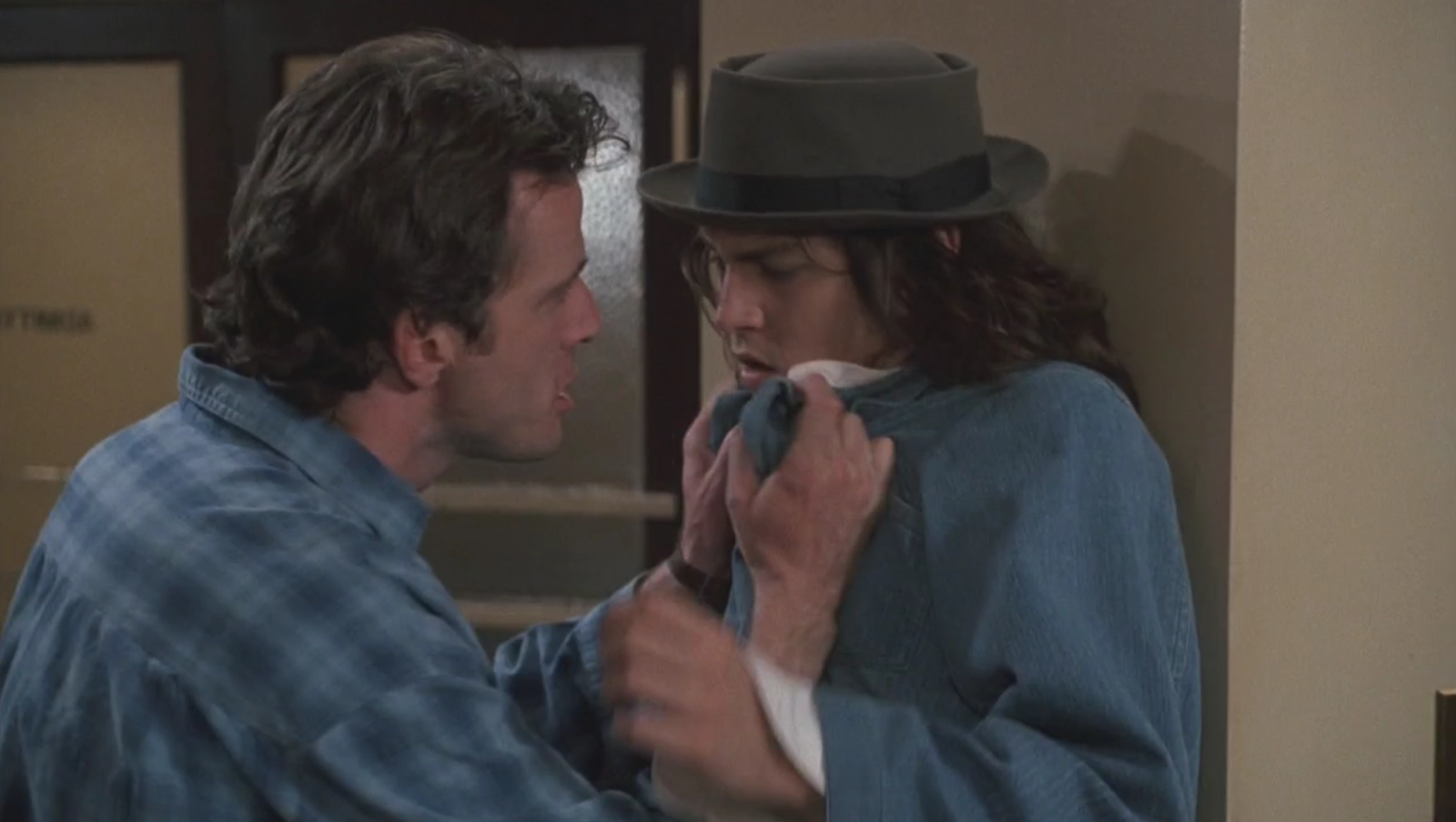

For example, Sam has been pursuing a job at the video store, where he hopes to capitalize on his special interest. But Benny thinks Sam should make a living as a performer. Sam resists this idea, and in the confrontation, Benny and Joon discuss Sam like he isn't there:

|

This is what addressing ableism looks like.

Benny comes off looking like a big huge jerk in this scene. |

"What is your problem?" Benny asks Joon. "This is his chance to do something, be somebody."

"He is somebody," Joon replies.

"Yeah, I know, but he wants to be more."

"You don't know what he wants."

The argument for autistic agency couldn't be any more clear. Joon is addressing Benny's tendency to infantilize Sam, and by extension, her. And since she's a strong female protagonist, she stands her ground against the onslaught.

Then Joon turns and invites Sam into the conversation, and the couple tells Benny, in not so many words, that they're "together".

Right on cue, Benny blatantly denies Joon the agency to choose who she loves. He violently kicks Sam out of the house. When she defends her rights, he becomes physically violent with her and decides he's going to send her to the group home, because she can't make good decisions.

Here she is robbed of agency in a very literal way: In the home, she will have no freedom or independence whatsoever.

|

Benny, after their fight: "Can I get you anything?"

In my head canon, Joon replies, "Yes. A new brother!" |

Benny's attitude is ableist and misogynist. It's the well-meaning paternalism that mentally and physically disabled people have come to expect from real people everywhere.

Ms. Tibbetts can't seem to see how she, too, reflects this attitude in her review, or how it denies us freedom, agency, love, and the ability to be represented with these qualities. She tries to speak for us in the same way Benny speaks for Sam and Joon, an allist who assumes she knows what we want, what media we should or shouldn't relate to or find meaning in, because she knows what's best for us.

And that makes her a Disability Ventriloquist.

This scene further drives home the point that our greatest problems come from allists who continually try to force us into unnatural and unfulfilling ways of being: whether it's in career direction, institutions, rigid social expectations, abusive teaching techniques, or through certain abusive therapies.

In a later confrontation with Sam, Benny becomes even more abusive. His behavior crosses the line into bullying territory as he is both violent and verbally cruel to Sam:

"You wanna know why everyone laughs at you, Sam? Because you're an idiot."

The comment stings in this context, and the word carries with it the harsh power it once had before it started being so casually tossed around. The same hurtful power

the "R" word still carries.

Just to be sure he's clear, Benny puts all the venom he possibly can into his voice and follows up with, "You're a first class moron."

|

| Oh no. You did NOT just say that. |

In response, Sam displays that uncanny human insight that we autists are often capable of. He looks past Benny's aggressive outward behavior and pinpoints Benny's deeper issue: "You're scared," he says. Then he asserts his agency and condemns Benny: "I used to look up to you. Now I can't look at you at all."

Sam's simple statement stops Benny. In that magical Hollywood moment, Benny realizes how he's mistreated Joon.

As soon as he sees her, he lets go of her, offering her autonomy, a chance to live on her own and to choose her own relationships.

"I'm through making decisions for you," he says, driving the theme home.

She rightly doesn't trust this change of heart, and during the ensuing argument, she displays the same uncanny autistic insight skill as Sam: "You need me to be sick," she accuses.

Of course this has been true in the past. But Benny has changed. When the doctor pressures Benny to put Joon in a group home ("Joon, we want what's best for you"), he gets his chance to prove his new course in the movie's final thematic pivot. He stops the doctor and says, "Why don't we ask Joon what she wants?"

Conclusion: Joon is a human being; stop treating her like a child.

The Feminist Angle

There are few women in this movie. Two men fight over the girl. These are good flaws to point out.

But I'm also of this opinion: No movie can, or should, escape every problematic trope. When you're throwing new ideas at an audience, you've got to stay focused. If you veer too far from what the audience expects, your point gets lost.

Here's a film that tackles the theme of disability in an impressive way. This argument would have been diluted with sisterhood themes, had Benny instead been Bernadette.

Moreover, we got to see a rarely depicted male character: a nurturing and loving brother who sacrifices money, relationships, and free time, to take care of his sister. This important portrayal helps defeat patriarchal macho-male stereotypes.

Or imagine if Sam was instead Samantha. In 1993, no one would have gone to see the movie, and even today, the disability theme would be completely obliterated by a more controversial LGBT theme.

Tibbetts criticizes the film for giving Sam's talents more screen time than Joon's. But we actually spend far more time following Joon. She is the first person we see, and Sam isn't even introduced until 20 minutes in. We already like her, so we don't need to see dwell on her talents. (Plus, it's kind of boring to watch someone paint.)

Sam is the

manic pixie dream boy, who exists solely to liberate Joon from her cloistered, sheltered life. We're not rooting for Sam to win Joon; we're rooting for Joon to win Sam. It's a reversal of the boy-meets-girl trope, so we're watching Sam through her gaze; we need to see what she likes about him.

|

So manic. So pixie.

#Swoon |

After all, she is the one doing the choosing. And that portrayal gets two thumbs up from this feminist.

Mental Health Services Are The Answer?

Ms. Tibbitts claims the movie doesn't show Joon getting treatment of any kind. I have to wonder if she fell asleep during the scenes with the aforementioned doctor. In one scene, Joon exits a personal session which I assumed was therapy. She is also on medication.

There is no reason to assume this suddenly stops just because Joon moves out. We might also hope they are able to get social services. Those details are the sort of boring minutia reserved for Wikipedia, government websites, and clinic pamphlets. Not for the ending of a movie.

Ms. Tibbitts' attitude seems to imply that getting help is easy and safe. It is not necessarily either. Most disabled people are pressed for money, professional help is expensive, insurance doesn't cover most of our needs, and social services are severely lacking and difficult to navigate, especially for people on the autistic spectrum.

Worse, there are many dangerous programs and therapies that cause more harm than good. Controversy surrounds even some commonly accepted practices.

|

A news story about abuses at the Judge Rotenberg Center

just last summer. Yes, including electroshock therapy. (Aug 2014) |

Moving into a group home is not all happiness and daisies. As the doctor in the movie says, "

These are very nice places," but they always say that. Institutions are often rife with all manner of abuses, ranging from

neglect (and

here), to

electroshock therapy, to outright beatings and

rape. It's nice to think those barbaric practices are a thing of the past, but we can't count on it.

Yes, therapy, meds, treatment are often beneficial. But it's dangerous to pretend these solutions are the answer for every autistic person. It bothers me to no end when allists carelessly toss them out as if it's all solved. It most certainly isn't.

For some autists, love is the only available answer. And many don't even have that.

Strong Disabled Female Character

Ms. Tibbetts' review concludes, "…the underlying message [is] that all Joon really needs is a stable romantic relationship rather than a stable relationship with herself, especially in relation to functioning in the outside world…"

|

Thanks for your concern Ms. Feminist Lady, but I like myself fine.

Oh, and also?

#Swoon |

Sorry, but Joon likes herself just fine, and neurotypicals be damned. She makes her choices and continues to assert herself against a powerful force that seeks to completely take away her freedom. Through meeting Sam, a fellow autist, she finalizes her already-begun self-actualization. She is liberated.

She isn't cured or changed. Instead, the world changes to allow her to live as she chooses.

This is what the neurodiversity and anti-ableism movement is fighting for. We wish to be accepted without having to force ourselves into the mold society expects of us.

Yet it's by this mold that the reviewer judges Joon. She implies that Joon isn't in a stable relationship with herself unless it's in relation to the neurotypical world. Her relation to herself, only to herself, as a hetro woman in love with another disabled person, letting him provide for her so she can make art, doesn't seem matter.

In the end, Joon and Sam don't let ableist messages control them. And neither will I. I won't let Disability Ventriloquists speak for me. No matter how well-intentioned they are.

Labels: art, ASD, Asperger's, Autism, character development, characters, empathy, feminism, fiction, intolerance, love, movie analysis, movie review, neuroscience, privilege, psychology, social justice, story, synesthesia